Deep Dive: “China + 1” Manufacturing and the Challenges of Processed Metal Dependence

Lies, Damned Lies, and Trade Flow Statistics

Deep Dive: “China + 1” Manufacturing and the Challenges of Processed Metal Dependence

Introduction

Amidst the background of geopolitical tensions and calls to decouple Western and Chinese supply chains, non-Chinese firms have been moving towards a “China + 1 strategy” of manufacturing. These firms are in the beginning stages of a process trying to reverse four decades of manufacturing migration to China and will undoubtedly face major challenges along the way.

In electronics manufacturing, the current “China + 1” model has not yet made its intended impact of streamlining supply chains away from Chinese products, due to China’s role in supplying processed metals to Southeast Asia. While American imports directly from China have declined since the beginning of the trade war and much of the slack picked up by Southeast Asia, this has not had the stabilizing effects on supply chains it might seem at first. US-ASEAN trade has certainly blossomed during this time, as manufacturing has relocated to the region, but Southeast Asian trade with China has also boomed over this time. This has led to a situation with more complicated supply chains, where Southeast Asia acts as an intermediary.

Almost all high-level electronics rely on a variety of minor metals during the manufacturing process, and processing capabilities for these metals are concentrated in China. The potential major disruption in China which prompted the move to Southeast Asia in the first place, be it environmental, political, or trade-related, would likely prevent those metals from being processed and exported, halting the supposedly deleveraged manufacturing in Southeast Asia. At present, firms have diversified midstream, but have not yet diversified upstream.

To be clear, this article is not assessing whether the “China + 1” strategy is desirable, although off the bat, it’s important to acknowledge that it undeniably requires firms to take short-term upfront costs. Instead, we are arguing that as supply lines are presently constructed, the attempt to derisk away from China by moving electronics manufacturing to Southeast Asia is not yet effective, because the metal inputs that go into those electronics are sourced from China. Furthermore, while it is possible that diversification could occur in the future, the current market conditions do not make significant expansion of non-Sino metal processing capabilities likely in the short term. A longer-term, more gradual view is needed.

What is “China + 1”

Since “China + 1” is a phenomenon that arose from many actors independently, the term is nebulous without a clear definition. However, if we are going to study it, then we require a working definition. Our “China + 1” definition is as follows: supply chain concerns regarding over-reliance on China prompting the decision to set up a factory in Southeast Asia or India.

This specific definition excludes cases in which there is migration due to the natural arc of economic development. These could include textiles migrating away from relatively higher-paid workers in Guangdong to Bangladesh or setting up a factory in India to get a foothold in that growing domestic market. While interesting, these are not cases of “China + 1” because firms are being enticed or pulled to other markets, rather than pushed from China.

The history of “China + 1” goes back to the early 2000s when it was mulled around in Japanese boardrooms after SARS disrupted supply chains. The strategy then rose to the forefront after China leveraged its singular position in the rare earth minerals supply chain to hamper Japanese industry, the exact example many firms are concerned about today. A 2011-2012 political spat over contested islands in the East China Sea sparked widespread protests in China and prompted China to cut off Japan from rare earth imports, hobbling the Japanese technology industry.

The strategy gained another life beginning in 2018 after the trade war began, when firms moved manufacturing outside of China to avoid US import tariffs. This accelerated the already existing trend of moving manufacturing to Southeast Asia. Imports to the US from China fell by almost 4% from 2018 to 2022, where the slack was picked up by ASEAN, and to a lesser extent, Taiwan, India and Mexico.

The pandemic also accelerated “China +1” plans, after global supply chain shortages and strong Chinese lockdown measures prompted firms to reconsider their supply chains. This, coupled with rising geopolitical tensions with the West, forced companies to build diversification plans. Concerns about supply chains from countries were again accelerated after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, when Western firms saw the full brunt of leaving a market at the drop of a hat. During this period, companies like Sony, Samsung, Adidas, Siemens, and Apple all announced plans to implement a “China + 1” strategy.

Sony has substantial electronics manufacturing hubs in both China and Southeast Asia.

Sony has had plants in Thailand and Malaysia for decades, which produce TVs, smartphones, cameras, and other consumer electronics. Sony has three more low-level semiconductor manufacturing plants in China, in Tianjin, Suzhou and Xi’an, alongside four in Korea.. Additionally, Sony recently announced that it will make a $70 million investment to build a factory producing automobile image sensors in central Thailand. A month after the announcement, Sony’s Weibo account in China was banned for a year after accusations that the Japanese company “insulted China” by defaming PRC martyr Qiu Shaoyun. This illustrates difficulties in a Chinese market where Sony is competing against lower-cost domestic Chinese competitors and facing marketing challenges that often follow Japanese companies in the PRC.

Samsung has already made the move. In 2019, Samsung stopped manufacturing phones in China, leaving the market entirely. Today most of Samsung’s phones are made in Thai Nguyen province in Vietnam, where the factories churn out more than 120 million phones annually. The South Korean giant also relocated major factories to other “+1” destinations. Their Indonesian factory opened in 2015, and a major expansion into Noida, India was inaugurated by both Korean President Moon Jae-In and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

In March, Siemens’ chief people and sustainability officer stated that Siemens was exploring adding factories in several Southeast Asian locations, including Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam. “With the world talking very much about the US and China from a diversification perspective, [Southeast Asia] is very interesting for us,” said the representative. Apple has been taking similar steps, which we will discuss later.

Lies, Damned Lies, and Trade Flow Statistics

As we mentioned before, the World Bank claims share of Chinese electronics in US imports has been steadily declining since the trade war began. Concurrently, Vietnam’s, Indonesia’s, and Thailand’s shares have all risen. And while electronics are the focus of this piece, there has also been a migration towards other goods as well, such as textiles. When it comes to manufacturing and supply chain resilience, it looks at the outset that Western, particularly American firms, have been deleveraged from China. But what this simple reading obscures is the massive boom in the Chinese-ASEAN trade that is helping create many of these goods.

Post-Trade War Change in share of US Imports (World Bank)

While China is assembling fewer of some goods, say phones, that find their way to Western consumers, China’s role as a supplier and processor of the world’s metals is as of yet unchanged from several years ago. The major difference is that, as manufacturing moves overseas, Chinese metals firms export that processed metal to the new factory in a foreign country, rather than ship it internally to factories in China. There have not been nearly enough metal processing facilities set up in Southeast Asia during this time to meet the increased local demand, nor would Southeast Asian be competitive with Chinese processed metal prices. This puts firms in a difficult position, where attempts to deleverage have been successful on the surface, through simple export numbers, but risks remain earlier in the supply chain. Given that the “China + 1” firms are, by definition, concerned about risks from China, either from geopolitical tensions or from government policy, then the metal reliance provides a difficult conundrum.

Southeast Asian Manufacturing Hubs: Value-Adding Midpoint

The Balkanization of the global supply chains has accelerated existing trends of moving electronic manufacturing to Southeast Asia, but the region as an electronic manufacturing hub is extremely reliant on international trade. Most of Southeast Asia’s manufacturing relies on inputs from abroad, and then exports the finished electronics internationally. Unlike China, most Southeast Asian countries are not large enough to have fully contained supply chains from ore processing to electronics manufacturing in-country, although even the domestic manufacturing behemoth China relies on international inputs for certain ores. This is a concern for those firms' diversification efforts because metal inputs are generally still sourced from China.

Countries like Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand are heavily reliant on the free flow of trade to continue the export segment of their economies. This trend has continued and accelerated since 2017, after the trade war and escalation of geopolitical tensions, with electronics manufacturers having announced major investments into assembly facilities in ASEAN.

One measure of this globalized nature in economics (don’t worry we are going to stay pretty simple here,), is the distinction between Backwards Participation Ratio and Forwards Participation Ratio. Backwards Participation Ratio measures the amount of value-added activity that takes place before the good is in the country. Looking at the Asian Development Bank’s measurements below, Singapore leads the way (unsurprising for an economically advanced trading hub), followed by Vietnam, where 40% of a good’s value predates its arrival in the country. Malaysia and Thailand follow it soon afterwards. What this tells us is that those countries are heavily reliant on importing semi-processed goods, like processed metals, for their manufacturing sector.

This in and of itself is not of huge concern, however, what takes this from notable to potentially concerning is the concentration of the suppliers. ASEAN has increasingly been attracting those major “China + 1” investors whose stated aim is to diversify away from the Chinese market. Yet at the same time, China is the key supplier in the manufacturing chains of those countries, especially true in metals as we will see below.

Participation Ratio per Asian Economy (Asian Development Bank)

China’s Role in Modern Metals: Magnesium Example

Today’s mining and metals world revolves around China, especially at the processing and smelting stages. We know that there are dozens of minor metals that go into smartphones, consumer and other electronic devices — metals which China has an almost singular capacity to refine and produce. China is often reliant on importing those raw materials, using most of them for domestic consumption, and then exporting value-added products. In this sense, China relies on the rest of the world for its raw metal needs, and the world relies on China for its processed metal needs. This interconnectedness in global supply chains means that, unless massive capital investment is made (and even in that case, geological luck plays a large role,) countries will continue to rely on each other.

Even if global supply chains do entirely balkanize into multiple blocks, this is a long and difficult process the present interconnectedness of the metals economy. Mines in Brazil produce niobium which is then sent to China to be processed alongside Australian iron to produce steel which is shipped to South Korea to make aircraft. And this is a relatively simple example relying on major metals. The expectations and the claims by business leaders that they are several years away from derisking should be taken with caution.

We can illustrate the point by examining one: magnesium. Magnesium is a low-density metal, similar to and often alloyed with, aluminum. The high durability alongside it’s light weight makes it a key component in many medical, automotive, aeronautic, and electronic manufacturing processes. Long story short, it’s an important, but often forgotten metal.

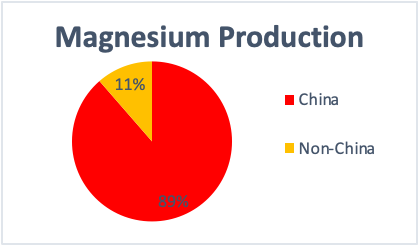

In this case, there are not issues sourcing raw magnesium. Given that it is globally available, and often in seawater, the opportunities to recover these are “virtually unlimited,” as per the US Geological Survey. However, despite these magnesium reserves, magnesium smelting and processing have concentrated in China over the last two decades. A mixture of cheaper prices, subsidized energy, environmental laws, and specialized expertise have drawn this production to China. As a result, China is processing approximately 83% of the world’s magnesium in the latest data from 2020 and 2021, with few alternative processing plants outside the country. Alternatively, the United States, only has one smelting facility, located in Utah, and does not hold strategic reserves, leaving importers to face difficult prices when the cost rose 300% in 2021. As we can see below Magnesium exports to “+ 1” countries have risen as manufacturing has relocated.

China’s Share of Magnesium Production.

Thai & Vietnamese Magnesium imports from China.

In this case, the question is not availability. However, even in this relatively mild case, in which access to raw materials is not an issue given its wide availability and the relatively uncomplicated smelting procedure, there would still be a multi-year lag to replace Chinese production should it fall offline. If a natural disaster, governmental issues, or political difficulties were to prevent the magnesium flow from coming out of China, an alternative processor would take 2-3 years to build. Other minerals, like rare earth elements, have mining concentrated in China, which provides even more centralized risk, and a longer timeframe to replace that supply since mines take a long time to open and the smelting process can be more chemically complicated.

Firm Case Study: Apple

But as these firms shift their supply chains to Southeast Asia, are manufacturing inputs moving with it? Supply chain data can be difficult to obtain and is not always public. That being said, there are also some creative workarounds.

After digging through some supply chain disclosures Apple had to make, due to the potential presence of conflict minerals, the author found a list of Chinese suppliers for those minerals. The graph below looks at tantalum sourcing. It is important to note that public disclosures for suppliers do not indicate the quantity of processed metals obtained from each processing station, it merely lists the contracted suppliers themselves.

Apple’s Suppliers of Processed Tantalum.

In this case, most of Apple’s suppliers of tantalum remain in China, despite attempts to source the metal internationally. Since the data we have says that 57% of Apple’s tantalum suppliers are in China, the actual quantity from China could be more or less concentrated than that, but we do not have access to the qualities shipped. Similar China-centric trends can be seen in the public disclosures of cobalt and other minerals for which we have data. It is difficult to perform research on these companies, because firms usually do not publicly provide their supply chain maps, but from the limited data we can see that this concentration seems to be an issue. Apple still sources its metal from China disproportionately, while very little processing is done in Southeast Asia (only 5% of their suppliers were in Southeast Asia.)

Solutions

There are several possible solutions for Western companies looking to deleverage and derisk more concretely and substantially. In the short term, without fail, each will be more expensive than the status quo, requiring more upfront costs for a case that might never be necessary, namely a disruption halting the Chinese export of processed metals. An attempt to deleverage or disconnect from the Chinese market is going to be difficult, even in the best and most justified scenario, sacrificing a massive amount of specialized productivity. That being said, those firms looking to pursue the strategy have several paths — investments in recycling facilities, stockpiling, and substitution.

Recycling

Many “China + 1” companies have made substantial metal recycling pledges unrelated to their China files, but recycling provides a wonderful opportunity to 一举两得/kill two birds with one stone. Our case study in the last section, Apple, has pledged to use only recycled rare earths, cobalt, tin, and gold plating by 2025. Samsung and Sony have also made recycled metal commitments, although those timetables are less specific.

The benefit of this solution is that these facilities already need to be built to hit those decarbonization targets. Rather than deploying large amounts of capital to build economically redundant metal processing plants outside of China, recycling facilities can be built outside China instead. This hits two birds with one stone — fulfilling ESG pledges while also decoupling.

Recycling cannot and will not entirely substitute for the mining and processing of new materials. Apple’s aggressive pledge to make iPhones carbon neutral is the result of its privilege as one of the world’s most successful companies, not aggressively battling for cost-conscious market share.

Most metal recycling does not happen in-house, but is contracted to other firms. If larger industry groups indicate that they are looking to shift towards metal sourced from ASEAN suppliers, then those facilities can be built at scale, giving them a sizable cost advantage. The ability to operate with a scale advantage is one of the reasons that metal processing has been slow to leave the Chinese market. “China + 1” firms could even begin to secure offtake agreements to give cost certainty to local metal processors, which would lower the cost of financing.

Substitutes and Stockpiles

Other potential solutions include stockpiling and substituting, although they requires upfront costs and will not work in all circumstances. Depending on the case, some of these metals might have substitutes that provide inferior, but similar functions. Magnesium, for example, can be substituted with aluminum or zinc in certain casted products, but this will generally make the product more expensive. Furthermore, for a company operating on a large scale, any changes in the production process become expensive hassles. And this is just the lucky case where there is a suitable, yet worse alternative. This becomes even more problematic when no substitute exists. In those cases, stockpiling might make more sense.

Stockpiling metals can be expensive, depending on the element, given that some metals cannot be stored for a long time without degrading. Stockpiling can also be expensive given the large cost to store metals, although this seems to be less of a problem with rarer niche metals than say, iron. This too seems like a targeted solution given the right commodity and firm, but is yet again, another upfront cost.

Overall, each of these options includes short-term costs, sustained costs in the case of building processing capacity outside of China, all done in the name of limiting potential volatile swings in the market. Ultimately, these acts need to be considered on a case-by-case basis. For a concentrated metal whose shortage would halt production and has a relatively cheap storage cost, it likely makes sense to stockpile. Concentrated minerals with cheap, available substitutes indicate that firms should prepare alternative production plans, to minimize disruptions should a switch become necessary.

Conclusion

Given the increasingly strained political ties between China and the West, it is understandable for firms to pursue lower-cost outsourcing that diversifies risks. Southeast Asia provides an attractive alternative, with low costs, solid infrastructure, and increasingly educated societies eager for economic development, all of which is why the region had already been a growing hub for electronics before this most recent swell of interest. That being said, it is important that audiences contextualize “China + 1” claims, and understand realistic timelines given the scale of this realignment. The metals industry is an extreme example of how intertwined the deeply complex global supply chains remain and how difficult a process full desrisking is, with a 2-3 timeline to build processing facilities if everything breaks right. Any attempt to remove China from global supply chains will take decades rather than years and firms will bear upfront investment costs to make those transitions. This long path cannot be solved by the end of the next calendar year.