Indonesian Export Restrictions, Processing Capability, and Chinese Partnerships

There’s a Party on Sulawesi and Everyone’s Invited

Hi folks,

Thanks again for subscribing. For our deep dive articles (of which this is one), I suggest reading on the website — they tend to be too long for comfort in email format.

Enjoy our first article about the intersection of policy, investment, and project management in Indonesian metals!

Best,

Zach

Indonesian Export Restrictions, Processing Capability, and Chinese Partnerships

There’s a Party on Sulawesi and Everyone’s Invited

This week’s Non Ferrous Flows surveys how different multinational companies are adapting to new Indonesian mineral export rules. We will also discuss the crucial role Chinese companies play in the country, both as individual investors and as joint partners alongside non-Chinese companies, especially in the nickel market. Nickel, critical for global decarbonization efforts, has been a massive driver of growth and foreign investment in Indonesia, which holds the largest reserves in the world. In the last two years, the value of Indonesian nickel exports has surged dramatically, from $3 billion to $30 billion. Indonesia’s unique role in the nickel market has put it front and centre, but similar export restrictions have been implemented over the last several years for other elements, and even more in the pipeline, like a copper ore ban coming in June.

The role of multinationals has been in the news after the well-publicized announcement last month that a multi-national consortium plans to invest $4.5 billion in an Indonesian nickel plant in Koalaka on the island of Sulawesi. While Ford received the most attention, reports indicate the American car manufacturer is only a junior partner in the deal, alongside Vale and majority owner China’s Huayou Cobalt. Furthermore, this dynamic of a Western investor partnering with a Chinese company to set up shop in Indonesia has been the norm during the recent expansion of Indonesian mineral processing over the last several years. We’ll discuss some other examples that look much like the Ford case below.

Rather than mining nickel ores and immediately exporting them, new governmental mandates are pushing miners to come up with mineral processing plans before sending nickel to international markets. With this in mind, how should companies plan for long-term project success? The rules and regulations regarding exporting Indonesian raw materials are rapidly evolving. For companies to maximize long-term profitability, firms must shift to having strong plans for localized mid-stream processing as well as mining. Put bluntly, if new laws limit the mobility of Indonesian ores, companies must stop thinking about the competitiveness of the mining operation and consider the competitiveness of the “mining and processing operation” as a unit.

This issue of Non Ferrous Flows will …

- Recap Indonesia’s new ore processing requirements and examine the motivations behind them

- Survey the landscape of Chinese metals (mostly nickel) companies, and the critical role they play in joint partnerships with non-Chinese, non-Indonesian firms

- Examine several challenges facing the new influx of Indonesian processing plants

Background and Political Context

Indonesia is well positioned for the green transition because it has enormous reserves of increasingly important minerals. Indonesia is the world’s biggest producer of nickel and also has major deposits of copper, bauxite, and tin. Traditionally, Indonesia has produced primary commodities, and shipped them out to other countries for processing, only to purchase them back from abroad as finished goods. Both the Indonesian political and business communities have been insistent in recent years that Indonesia must break this historical pattern and support value-adding activities. President Joko Widodo’s (commonly called Jokowi) government has centred it as a key tenant of developmental policy over the last several years. This movement up the value chain from raw materials to processed goods is seen as a lynchpin in the development success of other Asian countries, such as Japan, the Asian Tigers, and China. Jokowi has concentrated his national development strategy on restricting exports to improve domestic processing capability and attract Foreign Direct Investment. His government has estimated this shift up the value chain could bring in more than half a trillion dollars in new foreign investment over the next several years.

As Indonesian laws begin to require that more nickel processing take place inside the country, Indonesia will need to increase its capacity, and the associated capital has already started flowing in. Foreign direct investment in 2020 rose 44% year on year to $80 billion, and the value of Indonesia’s exported nickel products in 2023 was $30 billion, ten times higher than before the export ban. In 2021, the World Bank estimated that Indonesia’s 15 smelters generate 12% of global nickel refining capacity, trailing only China with 35%, but this is set to grow. Smelting investments have been pouring in as well — capital invested in North Maluku province’s nickel refining industry jumped almost 30% last year. The development of scalable commercial High-Pressure Acid Leaching (HPAL) as pioneered by Chinese companies means that Indonesian nickel deposits can now be refined for the high standards needed in EV batteries, so long as Indonesian authorities are willing to pay the environmental costs.

The Indonesian government side has been deeply involved in helping the industry develop over the past several years, both implementing new guidelines and prioritizing metal infrastructure projects. For example, the Bahodapi smelting plant, owned by a group of partners led by Vale, has been designated a National Strategic Project (Proyek Strategis Nasional or PSN.) Freeport McMoRan’s new “Manyar” smelter was built in a government-prioritized Special Economic Zone

As previously noted, Indonesia banned the exporting of nickel ore in 2020 to incentivize domestic processing. Indonesia had previously banned the exports of ore in 2014 temporarily, before working out a deal securing several miners’ intent to develop processing in-country. The Jokowi government is continuing this development strategy with plans to ban the export of both copper and bauxite in June 2023.

The goals of the government don’t stop at producing concentrates, however. The Indonesian government has been consistent that the EV revolution is a one-in-a-lifetime opportunity for a country well-endowed with green minerals, and the government wants to see the entire process begin to take shape. Jokowi has not been shy about trying to lure a Tesla gigafactory over the last several months and high-profile Minister of Investment Luhut Panjaitan commented that government-prioritized smelting plans fit into the “lithium battery production that we plan to [establish]”. From January to November last year, Indonesia exported 2.8 million tonnes of copper ore, ore which will soon need to be absorbed into the domestic smelting capacity when the copper export ban goes into place later this spring.

From a political perspective, Joko Widodo has regularly travelled to the openings of major smelters and mines, which underscores the political importance of these projects. Moving up the value chain is a key part of his political platform, and an area of personal importance to his political legacy as his time as president comes to an end in 2024. He has been a consistent presence at key events regarding Freeport, Vale, and Tsingshan, each multi-billion dollar investments that the government supports. This is part of Indonesia’s pitch wider to the business community as a welcoming place for international investment while maintaining strong boundaries of national sovereignty. The government has been positioning itself from a clear place of strength, knowing its resources make it a valuable place to invest, while also using government pull to fast-track international investments.

While the bulk of this action has been taking place in Indonesia, other countries in the region are considering following suit. The Philippines has publicly expressed a desire to follow Indonesia’s policy of restricting exports and building domestic refining capacity. In a recent interview with Bloomberg, Environment and Natural Resources Secretary Antonia Yulo Loyzaga stated, “We want to be part of the value chain,” and “There’s a range of actions including a progressive look at taxing exports.” On a more global scale, this has been a topic of conversation for developing countries with major mineral reserves, from the Democratic Republic of Congo’s cobalt to Zimbabwe’s lithium deposits over the previous year.

1. Chinese Firms

Chinese companies have been leading the way in building new processing capacity. In our first case, Chinese companies have been expanding Chinese-owned Indonesian smelting capacity since the 2014 wave of Indonesian export restrictions.

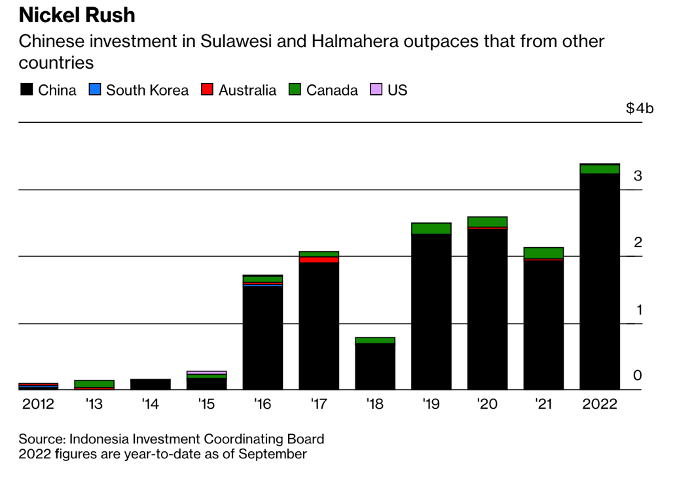

Bloomberg: International Investment in Indonesian Islands of Sulawesi and Halmahera.

Tsingshan

One important example of Chinese corporate involvement in Indonesia is Tsingshan Holding Group’s (青山控股集团) arc over the last several years. Tsingshan is the world’s largest producer of nickel and stainless steel, boosted by its innovative and cheap metallurgical strategies. The Financial Times article published last month outlines some of the technological breakthroughs over achieved over the last two decades, earning Xiang Guang the nickname “the Alchemist.”

Tsingshan has long roots in the country and has been building smelters to accord to local government restrictions for over a decade. Tsingshan started building Morowali Industrial Park, a massive metallurgical processing complex on Sulawesi Island, almost a decade ago in late 2013. Additionally, Tsingshan also built an entire thermal coal power plant to power the metallurgical park, using domestically-sourced Indonesian coal.

Financial Times: Processed Nickel Production in 2021

Tsingshan also built another sprawling mine-metallurgical processing in Weda Bay, where construction began in 2018 and finished in April 2020. Tsingshan became the controlling partner of the project after purchasing a substantial stake from French metallurgical company Eramet, who remains on as a junior partner. Reuters reported that Eramet was hesitant to move forward with the project after concerns about new tax rules and export restrictions in 2014. Freeport-McMoRan was in talks to build a multi-billion dollar copper smelting project in the same complex, before talks broke down in 2020, prompting Freeport to build elsewhere.

The company gained massive notoriety outside the nickel industry last March for its central role in the London Metals Exchange Nickel Scandal when trading was halted and trades reversed following a huge price spike. Bets made by Tsingshan founder and self-made billionaire Xiang Guangda went the wrong way, causing huge potential losses for the company before the trades were reversed — still the subject of massive controversy.

The turbulence of last year’s LME crisis hasn’t slowed the company down. Tsingshan and Huafeng Group (华峰集团) announced the signing of a new strategic partnership last November, where the companies agreed to jointly invest $3 billion to build a new nickel sulphate facility. The company ended mostly unscathed from the scandal last year and is poised to increase its share of the Nickel market in 2023.

Jiangsu Delong

Tsingshan is the most prominent Chinese company expanding its processing capacity in Indonesia, but it is not alone. Jiangsu Delong is the world’s second-largest producer of processed nickel and has also been extremely active in the Indonesian market over the last several years. Like Tsingshan, Jiangsu Delong’s smelting plant is already in operation. This smelter, PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry (GNI), opened in late 2021, after a capital investment of $2.7 billion. Located in southern Sulawesi this is expected to process 13 million tonnes of ore annually.

The world’s two largest Nickel producing companies are Chinese firms based in Indonesia, operating their own mining and processing plants. Whether this first-mover advantage will stick in the long run is unclear, but what we can say for sure is that Chinese firms are in an enviable position as other groups try and build processing capacity to accord with Indonesian export restrictions.

2. Chinese Joint Ventures

Chinese firms like Tsingshan have indicated that they are willing to both invest as part of a group, and on their own. This pattern does not hold for all Chinese firms. For instance, Huayou Cobalt has been more eager to invest alongside other partners. The main point of this section, however, is that non-Chinese companies, like Vale or Glencore, are not as eager to go in alone, and have instead operated on a joint partnership basis, alongside Chinese firms. As such, almost all projects in construction include Chinese expertise in one form or another. Seeing the projects below, the consortium of Huayou, Vale, and Ford investing in the Pomalaa project, announced last month is really just a continuation of recent trends.

Vale, Baowu, and Xinhai: Bahodopi

In February of 2023, Vale and its Chinese joint partners began building the Bahodopi ferronickel smelter in central Sulawesi. The Brazilian miner is working with two Chinese partners, Shandong Xinhai Technology Group Co. Lt and Baowu Steel. Vale is the biggest minority owner with 49% of the $2.1 billion. The project is also coming at an eventful time for the Brazilian company, as Vale ponders spinning off its base metal unit from its central iron ore portfolio.

The Bahodopi project has both speed and scale. The first stage was fast, going from signing the initial joint agreement between companies to shovels in the ground in under two years. Initial planning documents project the end of construction in 2025, and afterwards, the plant will be able to process up to 80,000 tons of ferronickel annually. More notable is that this new smelter is set up to be powered by LNG, rather than coal. Vale has committed to reducing its carbon emissions by one-third by 2030, and Baowu has pledged to cut 30% of its 2020 emissions by 2035.

Bakrie Group, Environ (Chinese) and Glencore

Indonesian Conglomerate Bakrie and Brothers is reportedly exploring options for an industrial park alongside Glencore and Envision, a Chinese energy company. The consortium, called the Indo-Pacific Net-Zero Battery-Materials Consortium, wants to purchase 2,000 hectares of land in Sulawesi and a mine with a 25-year lifespan. According to public comments made by Bakrie executives, they aim to create a one-stop full value chain, from smelting to manufacturing batteries, costing approximately $9 billion. More developments are expected later this year, as studies proceed into spring.

3. Without Chinese Partners: Freeport-McMoRan

Freeport-McMoRan is one example of an international corporation building Indonesian smelting capacity without Chinese help, although it is doing this in the copper space rather than nickel. After negotiations to build a joint copper smelter with Tsingshan broke down in 2020, Freeport-McMoRan decided to build it on its own, with some operational assistance from Japanese Chiyoda International.

The Indonesian arm of Freeport McMoRan is majority owned by the government. It has a long history in the country and has already invested in new smelting capacity. Freeport had previously built a smelting plant named “PT Smelter” in the 1990s to comply with local regulations, so the new “Manyar Smelter” facility will be the second that Freeport has in the country. The mining licence Freeport received from the government in 2018 gave them rights to operate the mine until 2031, with an extension until 2041 if it built a new smelting facility. New rules overtook that initial ruling as Jokowi’s government began to implement new domestic processing requirements in 2019 and afterwards, functionally making domestic copper smelting a requirement. Interestingly, Freeport rejected government pressure in 2020 to enter a joint venture with Tsingshan and build the smelter at Wada Bay, indicating that there is some give and take between the government and foreign businesses.

Reuters reported: “The $3 billion facility in Gresik, East Java, will have a capacity of 1.7 million tonnes of copper concentrate and is expected to start operations gradually in 2024.” The smelter, located in a newly deemed Special Economic Zone, expects to put out 550,000 tonnes of copper cathode annually, potentially reaching up to 600,000 tonnes according to CEO Tony Wenas. The project, which started production in October 2021 recently passed the halfway point in its building process and hopes to be finished by the end of 2023.

The site of the East Java smelter is a newly announced special economic zone near the major city of Surabaya. The complex, the “Java Integrated Industrial Port and Estate,” already has hookups to natural gas pipelines, port access, and wastewater and is presently expanding electricity capacity. Additionally, the SEZ plans to incorporate “Renewable Energy to match demand,” although the details are not yet public. Operating within a larger industrial bloc as part of a SEZ is positive news for smelting energy usage. Centering the smelter at an industrial-hub reduces both transport and energy costs since energy sources can be built at scale, bringing down per-unit costs. Furthermore, the lack of coal in the SEZ’s stated energy policy stands out in a country powered primarily by coal. As global banks, car manufacturers, and industrial firms aim to reduce their carbon footprint, processing using greener energy, or at least natural gas, could be the key to ensuring a customer base.

Freeport is an interesting counterfactual to the other non-Chinese international firms looking to build processing capacity in Indonesia without partnerships. However, Freeport has three major differences from firms considering expansion. Firstly, Freeport has long roots in the country, having been there since the 1970s. This matters because the relationships with local stakeholders, cultural awareness, comfortability in the region, and relationships with the national government take a long period to cultivate. The comfort needed to invest billions of dollars into a country often takes time to build.

Secondly, Freeport is processing copper, not nickel. Much of the desire to partner with other firms is to leverage their expertise, and the metallurgical nickel processing advancements made by Chinese companies over the last two decades bring the most financially-competitive metallurgy (like the previously mentioned High-Pressure Acid Leaching processes) to the partnership. This is not necessarily the same as copper, meaning there would be a smaller value added to a Chinese partnership in the copper context.

Thirdly, and most importantly, while Freeport-McMoRan is an American company, the Indonesian subsidiary is majority owned by the Indonesian government and is thus subject to major Indonesian government control. The Indonesian SOE Inalum (PT Indonesia Asahan Aluminum) increased their stake in Freeport’s Indonesian subsidiary in late 2018, achieving majority ownership. This means that boardrooms are giving up both control and authority in exchange for access to deposits. This takes us back to the first point, which is that giving up this kind of control to a foreign government is much easier with a relationship built over decades, as Freeport has done.

Challenges: WTO

In 2019, the European Union challenged Indonesia’s then-upcoming ban on raw nickel exports in the World Trade Organization. The EU argued that the ban unfairly disadvantaged Europe’s stainless steel industry. In November last year, the WTO ruled in Europe’s favour, deciding that both the raw export ban and domestic processing requirement violated WTO rules.

Put bluntly, the Indonesian government has given no indication that this legal challenge will change their policy in any meaningful way. In response to the result, Jokowi stated, "Even though we lost at the WTO on this nickel issue... it's okay. I have told the minister to appeal.” Indonesia formally launched an appeal the following month, in December 2022. Despite this public loss, Jokowi plans to impose a similar ban on copper and bauxite in June, and tin at some point in the future. He has repeatedly stressed that his priority is to the Indonesian people and moving his country further up the value chain. At this point, it does not seem that the slow-moving process of the WTO ruling will have much impact, at least in the short term.

Challenges: Green Processing

Indonesia’s Minister of Investment, Bahlil Lahadalia noted in January that Indonesia plans to put in new energy restrictions on smelters to ensure that projects going forward rely on green energy.

At this point, messaging from the government regarding smelting capacity restrictions should be taken seriously, but questions about the timeline remain. On one hand, the government has already demonstrated a level of comfort in guiding policy and strongly implementing their development vision. New government rulings regarding export controls are why Indonesian smelting capacity is an issue to begin with. On the other hand, green talk is easy, and many plans fall by the wayside when economic and political circumstances change. If the Indonesian government wants to shrink the capacity to extend the lifetime of its high-grade nickel reserves or keep a buoyant price, limiting smelters who do not contribute to carbon goals would be an effective differentiator to decide between projects. This means that investment in green projects might not just be a positive for its own sake, but could become a requirement to enter the market.

Furthermore, without new benchmarks encouraging greener processing, Indonesian nickel could be at a competitive disadvantage in the global market if the carbon footprint of nickel becomes a priority for buyers. Estimates show that Indonesian nickel is up to five times more carbon-intensive than nickel produced in Canada or Australia. As corporations start to impose carbon reduction targets, and banks limit the carbon footprint of their lending, coal-intensive nickel could see a reduced market or at least a discounted price on the increasingly carbon-conscious market. Vale’s Bahodop plant's movement towards LNG indicates that companies are already considering the carbon intensity of their footprint.

A combination of government standards and market demand for less carbon-intensive nickel will push Indonesia towards greener nickel, but at what pace? The governance question requires some waiting and monitoring communication from the government, while the latter requires more research.

Takeaways and Market Implications

Companies and investors should ask, “Does an adequate opportunity exist for building and sustaining a successful refinery that is carbon-competitive in Indonesia?” A valuable deposit, strong staff, and supportive community are not enough — successful mining in Indonesia now requires a realistic processing plan as well. Given Chinese experience in metal and especially nickel processing, this has positioned Chinese companies well, because Chinese processing know-how has become a valuable asset for other firms investing in the country. This is one of the main reasons joint partnership have becomes so common.

That being said, in some ways, this can be a valuable opportunity. Companies involved in mining and mineral resources extraction are engaging in a long-term partnership with the host government and community. Well-run mining companies already have long-term relationship-building skills, and providing fair employment to local populations in well-managed smelters can boost community support for mining companies. This article has provided a few different examples of how foreign companies in Indonesia are adapting to the new processing requirements. The next step is determining how well companies can adapt to the government’s new regulations, and the global market’s stricter carbon accounting. In the meantime, in addition to seeing mining and smelting as a package, companies must increasingly consider the forms of energy that power these investments as a critical input cost — it seems likely to become increasingly important in carbon-conscious boardrooms.